It was an honour to be invited to give the closing keynote at LITA Forum. I have never been asked to do a keynote, so I was equal parts terrified and excited.

Here’s the text from my talk. I’d love to know what you think: @tararobertson on Twitter or email me.

Note: the Creative Commons license for these slides differs from the rest of the content on this site. These slides are licensed with an Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license as they contain extended quotes that are not mine, and while most of the of the images are CC-BY licensed, several are not.

Land acknowledgement

I am from Vancouver, Canada which is the unceded traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations. Unceded means that the land was never sold, given, or released to any colonial government. In Canada we’re thinking a lot about relationships between settlers and First Nations in many areas of society.

In Canada we’re still deeply feeling the effects of colonization and the effects of Residential Schools where the church and state tried together to “kill the Indian in the child”. Through the process of Truth and Reconciliation we’ve witnessed the stories of people who survived and heard about the massive amount of physical, sexual and emotional abuse that occurred. The Truth and Reconciliation Report called this cultural genocide. Despite systemic efforts from the church and the state to erase Aboriginal people in Canada these nations and cultures continue to persevere, resist, and First Nations and settlers are actively working to break the cycle of violence and trauma.

I’m half-Japanese-Canadian and my family was interned during WWII in Canada. So for me a settler, learning and naming whose land I’m on is a small thing that I’m committed to doing as part of the process of decolonization and reconciliation with First Nations.

Even with the help of several librarians I wasn’t able to find out whose homeland we have been conferencing on. If you know, I’d love to learn how to appropriately acknowledge this.

Choi+Shine Architects. The Land of Giants. (used with permission)

Introduction

For me the land impacts my thinking quite a bit. While I was born in Vancouver, I grew up in a northern logging town halfway between Washington state and Alaska. While I live in a city now, a lot of the technology work I’ve done supports people in rural areas and seeks to bridge the digital divide.

I’ve worked in libraries for 13 years, 9 of which I’ve been a librarian. I’ve worked doing training and support for small public libraries who migrated to Evergreen, an open source ILS. I’ve worked as a systems librarian at a small art and design college, and currently do accessibility work to remove barriers for students with print disabilities by format shifting their textbooks.

I love this image from Choi+Shine Architects’ concept drawings for powerlines in Iceland. I feel like this photo illustrates the technology work I’ve done in libraries. When having a imposter syndrome moment at a conference, a colleague said, “I think of the technology work you do is the last mile”. So, while I’m not at the front breaking new ground and innovating, I’m chugging along behind making sure everyone can access information.

I became a librarian because I’m passionate about access to information. My core values are around “open”: open source, open access, open textbooks and open education. So, why am I arguing that all information should not be accessible?

Before I get into that, I’d like to tell you about one of my favourite writers.

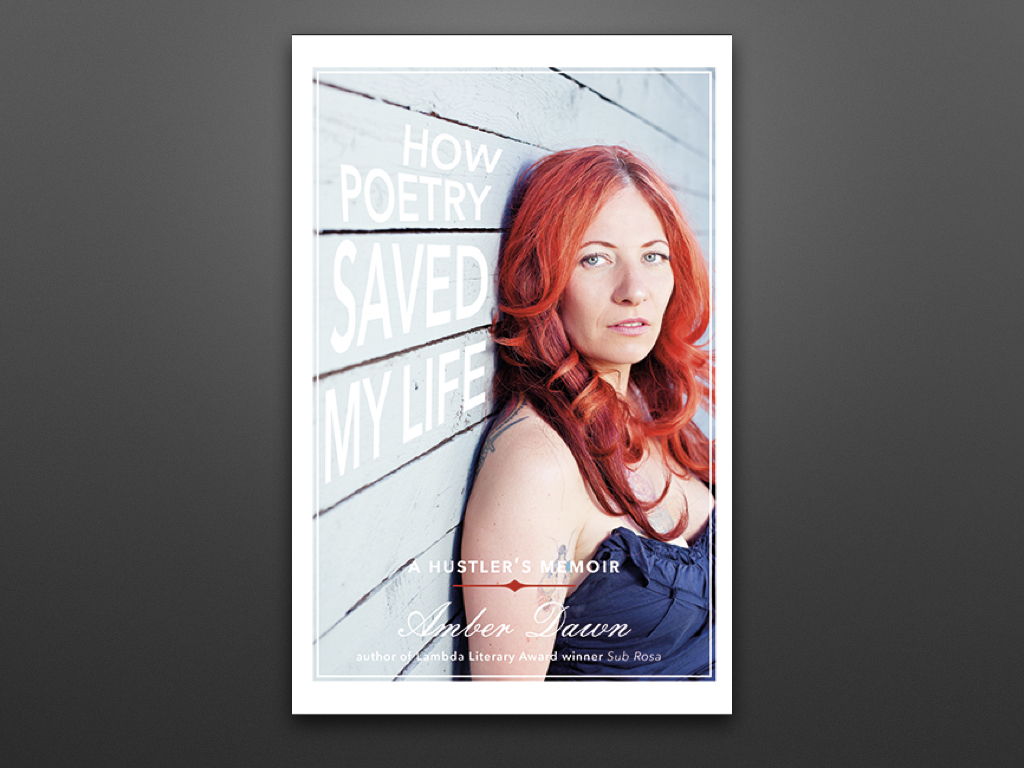

Amber Dawn

Amber Dawn is a writer, a poet, and a creative writing instructor at a couple of universities and in community driven art and healing spaces.

In the preface to How Poetry Saved My Life: A Hustler’s Memoir, she writes:

…my writing does not stand on its own. My writing is comprised of the lives, deaths, struggles, and the work, accomplishments, alliances, and love of many. My writing is indebted to queers and feminists, sex workers and radical culture makers, nonconformists and trailblazers, artists and healers, missing women and justice fighters. My writing stands with those who also have been asked—in one way or another—to edit their bios.

Thank you

I feel a great deal of gratitude towards many people who inspire me and have my back.

I’m one of those annoying extroverts who needs to think out loud. I appreciate the generosity that all of these people have extended to me. These people are friends, colleagues, comrades, librarians, sex worker activists, academics, feminists, queers, artists and pornographers. I think it’s important for me to acknowledge all of these people as extended feminist citation practice but also because I wouldn’t have the courage to speak today. I’m standing on the shoulders of these giants.

I feel privileged to talk to you today about some of the ethical issues I’m concerned about in digitization. For me I need to step out of my comfort and safety of being a professional and share my personal stake in this conversation.

Amber Dawn writes:

If comfort or credibility is to be gained by omitting parts of myself, then I don’t want comfort or credibility. I am not ashamed of my bio. What would be a shame is if I were to fall silent. Each time I bring my fingers to the keyboard, I join the many who also seek to explore and discover seldom-told stories, speak the tough and tender words that are too rarely articulated in day-to-day discourse, and create that place where we have permission to express emotions.

Red umbrellas

The first time I did sex work, I was 19 years old and studying Japanese at the University of Victoria. I was a macho third wave feminist and I was broke. I dipped in and out of different types of sex work over the next 15 years, usually while doing some other straight job as well. I worked at Legal Aid while I worked at a BDSM brothel and worked at the public library while I worked as an escort. My shame kept these two work lives very separate and I was unable to speak to many people about my experiences. I don’t think sex work is shameful work, but the judgements and assumptions that are made about sex workers has made me wary and careful about where I’ve talked about these parts of my life.

Until very recently this isn’t something that I ever talked about.

It’s interesting to be a stealth about my sex work history while working in higher education. I’ve heard a lot of very educated people say some very ignorant things when they were describing sex workers with simplistic stereotypes. At last year’s Open Ed conference the participant swag were red umbrellas. It rains a lot in Vancouver, so that makes sense. What the organizers didn’t know is that red umbrellas are the symbol for sex worker rights.

Montreal Out Games, 2006

When I was working at the public library as a library assistant I was selected to represent my union at an international LGBT labour union conference in Montreal that was part of the Out Games. One of the goals was to produce a proclamation on LGBT human rights. We met in various caucus groups to learn about issues from different countries and the issues facing workers in different industries.

The plenary took place in a large, generic, beige conference room with a panel at the front of the room on the stage, mic in the middle of the centre aisle, and the simultaneous translation booths at the back. In the caucus meetings leading up to the plenary I’d listened to many of the older feminist union leaders talking about us sex workers as pitiful and naive victims who were undeserving of workplace protections.

I hadn’t planned on speaking, so I’m not sure how I ended up at the mic. My hands and my voice were shaking. I remember introducing myself as a feminist, a sex worker and a library worker. I said inherent in the phrase “sex worker” was that we were workers and like all workers should be entitled to a safe and respectful workplace. After I felt super overwhelmed and my hearing started to go, like it does before I black out. Through my inadequate high school French and some professional translators I had a passionate discussion with some of the feminist leaders of the Quebec labour movement who had done a 180 and were now supporting including explicit protections for sex workers in the proclamation. Svend Robinson (that’s me and him in the top left photo), Canada’s first openly gay national politician, crossed the floor and gave me a big hug and told me how proud he was of me for strategically coming out to facilitate a more inclusive proclamation. Speaking from my experience was really powerful for me because I changed people’s attitudes about sex workers.

ProQuest: Canadian Major Dailies

What I didn’t know was that a reporter from the Montreal Gazette was in the room. The next morning while reading the newspaper I almost threw up when I saw I had been quoted in the newspaper as “Tara Robertson, Vancouver public librarian and former sex worker”.

Honestly about half my fear was the wrath of librarians policing the border between paraprofessionals, which I was, and their credentialed selves. The various types of sex work I had done had always been under a pseudonym and with the makeup and wigs, I wasn’t easily recognized as my library worker persona. I was angry and scared. I didn’t know that there were media in the room and I hadn’t intended to come out, let alone make a public, searchable record of it.

The Montreal Gazette is indexed in a couple of ProQuest databases. My biggest fear, earlier in my career, was that I would be outed through a thorough reference check for a job. People would be searching for “Tara Robertson and libraries” and discover that I was a former sex worker. This is one of the reasons that I purchased my website domain when I was a library school student. I wanted to do what I could to control what came up when people searched for me.

I didn’t have the courage to retrieve this article until earlier this year.

Reflect

This is a self reflection exercise and I will not be asking you to share your thoughts out loud with other people. For the next minute you may want to close your eyes. I’d like you to think about a time when you felt shame.

What caused this shame? Where do you feel shame in your body? Who has seen your shame? What would it be like if your shame was public?

On Our Backs

I know firsthand what it’s like to have information on the internet that I didn’t consent to, the fear that it could harm my career, and the double standard against women’s sexuality in our culture.

In March of this year I learned that Reveal Digital has digitized On Our Backs, a lesbian porn magazine that ran from 1984-2004. It had actually been online for several years before I learned about it. For a brief moment I was really excited — porn that was nostalgic for me was online! Then I quickly thought about friends who appeared in this magazine before the internet existed. I was worried that this kind of exposure could be personally or professionally harmful for them.

While Reveal Digital claims to have gone through the proper steps to get permission from the copyright holder, there are ethical issues with digitizing collections like this. Consenting to a porn shoot that would be in a queer print magazine is a different thing to consenting to have your porn shoot be available online.

I talked to a few people I know who modelled and they generously agreed to give me quotes to use in this talk.

Quote #1

From the first discussion with the editors, I knew I had to weigh what appearing in the magazine might cost me in my work and community life. But at the time, I felt that the magazine had a small print run, and was sold in queer spaces to queer audiences.

When I realized the distribution was broader, I requested that my name not be added to metadata, and tried to do my best to protect myself. The editors respected my request and even had the UK distributor edit their tags and metadata for me.

Quote #1 continued

When I heard all the issues of the magazine are being digitized, my heart sank. I meant this work to be for my community and now I am being objectified in a way that I have no control over. People can cut up my body and make it a collage. My professional and public life can be high jacked. These are uses I never intended and I still don’t want.

Quote #2

I actually never consented to have my photoshoot published in On Our Backs in print, in 2002. My ex and I were in a photoshoot specifically for a photographer’s book on kink in 1993—before the first web browser was released!—and signed a model contract for limited use. So 9 years later, I felt fairly fucked over to discover this shoot in On Our Backs–with our real names on the cover–after it had already been out for over a month.

This person works in the tech industry and as a queer woman has to work harder to be taken seriously as an expert in her field. She’s worried that if this is digitized, with her name on the cover, it’ll impact what is searchable under her name.

Quote #2 continued

“It’s one thing to have regrets over what you’ve published, but I actually never consented to have this photoshoot published by On Our Backs in the first place, let alone digitally.”

Quote from Amber Dawn

In 2005, I co-edited a queer erotica anthology titled With A Rough Tongue: Femmes Write Porn. The collection marked many things for me, the most significant of which was my coming out as a queer, femme sex worker and survivor within published writing. I was motivated by the growing number of mentors and peers who had spoken up before me, and also by the much larger number of sex workers and survivors I knew who did not have the privilege or ability to speak up. The evolving sex-positive and social justice values of the mid-2000s did not protect me from fear and stigma I faced coming out. Backlash, I discovered, was very real consequence. I quickly learned importance of making strategic and self-caring choices about where to use my voice and body.”

Some early decisions Amber Dawn made for herself included:

- to only speak, publish or showcase body art in forums where she can directly speak to and negotiate with the editor or curator,

- where she understands the intended audience to be communities that share similar sex-positive and social justice values and

- where she has the ability to directly connect with audiences and foster future respectful dialogue.

Amber Dawn says that choosing to appear in OOB in 2005 allowed her to adhere 3 of these conditions.

Quote from Amber Dawn continued

Years later, the digitization of On Our Backs strips me of all three. What was once a dignified choice now feels like a violation of my body, my voice and my right to choose. In no small way is the digitization a perpetuation of how sex workers, survivors and queer bodies have been historically and pervasively coopted. How larger, often institutional, forces have made decisions without consulting us or considering our personal well-being.

Ethics of care

These three quotes clearly illustrate that these people had clear ideas about the content, how they wanted it viewed and used. They all have sophisticated and nuanced understandings of media representation and how they wanted to be represented.

The consent issues here are dodgy. For the first woman there was an agreement that this content would never be online. For the second woman there was no consent given to even appear in the magazine. For Amber Dawn having OOB digitized and put online violated the conditions that she had decided were critical for her.

Even the copyright issue is complicated: the photographer would’ve held copyright, not the models. The photographer would’ve then either handed over copyright to the magazine, signed over copyright for a specified time period, or agreed to have them published and retained copyright. OOB doesn’t exist anymore, so it takes some sleuthing to track down who now owns the rights. When I was at Cornell I visited the Rare Book and Manuscripts Collection to sift through Susie Bright’s papers. Susie Bright is a sex positive feminist who cofounded and edited OOB from 1984-1991. I found copies of contributor agreements. Some of them were for one time rights only, or for first time North American serial rights, or for a period of one year from a specific date.

In talking to some queer pornographers, I’ve learned that some of their former models are now elementary school teachers, clergy, professors, child care workers, lawyers, mechanics, health care professionals, bus drivers and librarians. We live and work in a society that is homophobic and not sex positive. This could negatively impact many people’s careers and lives.

When I brought up these concerns in March the most common critique from librarians was about our responsibility to be good stewards of our collections. A few librarians viewed this as limit on open access and worried about censorship. A year ago these would’ve been the same points that I would have made.

We talk about our responsibility to the collections, but what about our responsibility to communities. In this case I found myself caught between my profession and one of my communities, and I noticed that my opinion changed. “The community” wasn’t an abstract notion, it was the people who gave me those generous quotes. I could see their faces and empathize with their fears and feelings that institutions had screwed them over again.

If you haven’t read Bethany Nowviskie’s piece on Capacity and Care I highly recommend it. In discussing the application of an ethic of care Nowviskie says:

…let’s create more cultural heritage platforms that promote an understanding of the vulnerability of the individual person and object. Let our visualization systems more beautifully express the relationship of parts, one to another and to many a greater whole.

Reveal Digital takes down OOB

On August 24, 2016 Reveal Digital announced that they were temporarily removing access to the OOB content. The main reason they gave was took this collection down citing minors access to pornography, the privacy concerns I raised and the need to consult with community.

I was happy to hear that they had removed this content from the web, even if it is temporarily. However, I feel very conflicted about the work that Reveal Digital is doing. On one hand I admire that they’ve figured out a unique business model and a way to work with libraries to digitize and make independent media accessible on the web. On the other hand I feel that naming restricting access to minors as the first reason for why On Our Backs as been temporarily removed is odd. While citing the Greenberg v. National Geographic Society ruling Reveal Digital says it gives “the legal right to create a faithful digital reproduction of the publication, without the need to obtain permissions from individual contributors”. When I first started talking to them about my concerns they defined community narrowly, basically as the libraries that are funding their work. Thankfully they’ve broadened their idea of community in this instance to include “publishers, contributors, libraries, archives, researchers, and others”.

In an interview in The Charleston Advisor Peggy Glahn, Project Manager at Reveal Digital, stated that future projects will focus on zines. She said that they would be “working in close partnership with librarians who are currently following the Zine Librarians Code of Ethics and intend to be in full compliance with this document when we do work with zine content.” This statement is a bit odd for me as the Zine Librarians Code of Ethics is not a technical standard or legal code that one could be in full compliance with. The Zine Librarians Code of Ethics says “This document aims to support you in asking questions, rather than to provide definitive answers.”

Zine Librarians Code of Ethics

We need to have an in depth discussion about the ethics of digitization in libraries. The Zine Librarians Code of Ethics is the best discussion of these issues that I’ve read. There are two ideas that are relevant to my concerns are about consent and balancing interests between access to the collection and respect for individuals.

Zines are often highly personal and some authors might find the wider exposure exciting, but others might find it unwelcome.

For example, a zinester who wrote about questioning their sexuality as a young person in a zine distributed to their friends may object to having that material available to patrons in a library, or a particular zinester, as a countercultural creator, may object to having their zine in a government or academic institution.

The Zine Librarians Code of Ethics does a great job of articulating the tension that sometimes exists between making content available and the safety and privacy of the content creators:

Librarians and archivists should consider that making zines discoverable on the Web or in local catalogs and databases could have impacts on creators – anything from mild embarrassment to the divulging of dangerous personal information.” Zine librarians/archivists should strive to make zines as discoverable as possible, while also respecting the safety and privacy of their creators.

Delgamuukw Trial Transcripts

Here’s another example of something that shouldn’t have been digitized.

The Supreme Court of Canada decision in the Delgamuukw case (PDF) in 1997 is widely seen as a landmark case for treaty negotiations. During the trial Delgamuukw elders testified and shared information that would not normally be shared outside their community. They chose to break cultural protocols for the greater good of their community’s land rights. As this was in the courts their testimonies were part of the court record.

These trial transcripts are widely available in print in law libraries across Canada. At the request of UBC’s Law Library they were digitized. As you can see in the screenshot, these are part of UBC’s “Open Collections”.

Even though these materials are widely available in print at law libraries across Canada, some people believe that UBC should not have digitized this collection. There was an acknowledgement that a policy is needed, but this collection is still up while there’s slow progress towards writing the overall policy. UBC should take this collection down while they consult with the nations whose traditional knowledge was put online without their consent.

Mukurtu

So, I’ve showed you a couple of examples of digitization projects that I consider really problematic. What’s a better way to do this?

Mukurtu is a Warumungu word meaning a safe keeping place for sacred materials. The Warumungu are a group of Indigenous people in Australia.

Mukurtu is an awesome grassroots project aiming to empower communities to manage, share, preserve, and exchange their digital heritage in culturally relevant and ethically-minded ways. It’s open source and community driven. The top priority is to help build a platform that fosters relationships of respect and trust.

Mukurtu allows you to set up complex permissions, for both digital objects and users, so that the digital access mirrors existing cultural protocols around accessing information. I also love how the community can contribute metadata alongside our spare institutional metadata.

This summer I attended one of their twice monthly online office hour sessions. This is a great strategy for open source software projects. It’s really accessible, welcoming and while documentation is good, it’s great to talk to someone who really knows the software. Alex Merrill did a great demo and was able to answer all of my questions about how permissions work.

Traditional knowledge (TK)

I was at a loss of what to put for an image here. I thought of a variety of First Nations technologies, and then decided it was best to leave it blank. These aren’t my cultural traditions and it didn’t feel like it was my place to pick an image for this slide.

I’ve read several of Greg Younging’s publications on traditional knowledge and copyright. I love the ideas he’s introduced me to and how accessible his writing is.

In the recently released (July 2016) IFLA publication Indigenous Notions of Ownership and Libraries, Archives and Museums he has a chapter where he gives many examples of customary laws around the use of traditional knowledge. These vary greatly between indigenous nations and include:

- certain plant harvesting, songs, dances, stories, and dramatic performances

which can only be performed/recited in certain settings, seasons and for certain cultural reasons; - artistic aspects of TK, such as songs, dances, stories, dramatic performances, and herbal and medicinal techniques which can only be shared in certain settings or spiritual ceremonies with individuals who have earned, inherited, or gone through a cultural or educational process.

These are just two examples, Younging identifies several more.

Younging lists 3 major ways that TK and Western system of intellectual property rights clash:

- that expressions of TK often cannot qualify for protection because they are too old and are, therefore, supposedly in the public domain;

- that the “author” of the material is often not identifiable and there is thus no “rights holder” in the usual sense of the term;

- that TK is owned “collectively” by indigenous groups for cultural claims and not by individuals or corporations for economic claims.

So, what is a good way to respond to these conflicts?

TK labels

There are some TK licenses that have been developed for when people own the copyright for their traditional knowledge. But what about cases where someone else, like a museum or a library holds the copyright to traditional knowledge that belongs to an Indigenous group? TK labels were designed for this scenario. TK labels are educational and informational. They are not legal tools.

I watched a video of Kim Christen Withey speaking on TK. She says:

Many Indigenous knowledge systems rely on protocols. Many of the protocols have to do with *not* seeing, which very much is the antithesis of the Western “seeing is believing”. You have to see it to know it. And these systems are saying you don’t get to see it or know it—deal with it.

Last summer I went to the c̓əsnaʔəm exhibition where the Musqueam nation told the story of their history and culture in their own words. One of the most impactful things was a display case with photo of a bowl. The actual bowl wasn’t inside. The explanation read:

Our relationships with the spiritual and sacred world are personal and private. Some belongings, such as those used in ceremonies and the ornate stone bowls used for mixing medicines, were the property of powerful ritualists who lived at c̓əsnaʔəm. These belongings remain spiritually potent and can be dangerous. They must not be touched or viewed by people who do not have the proper ritual training, hereditary privileges, or ceremonial knowledge.

Like Kim Christen Withey said “you don’t get to see it, deal with it”.

At localcontexts.org they explain that working with the community is necessary to use TK labels:

Using the TK Labels requires community decision-making. This is especially the case for cultural material that is not owned individually but should be managed collectively by your local community. The decision-making processes for using these TK Labels should be established before you choose which labels will suit your needs. The TK Labels can also facilitate dialogue about what options are more appropriate for your local context, and what kinds of conversations need to happen before even using or developing the TK Labels. Each family, clan or community will have different processes and frameworks for decision-making.

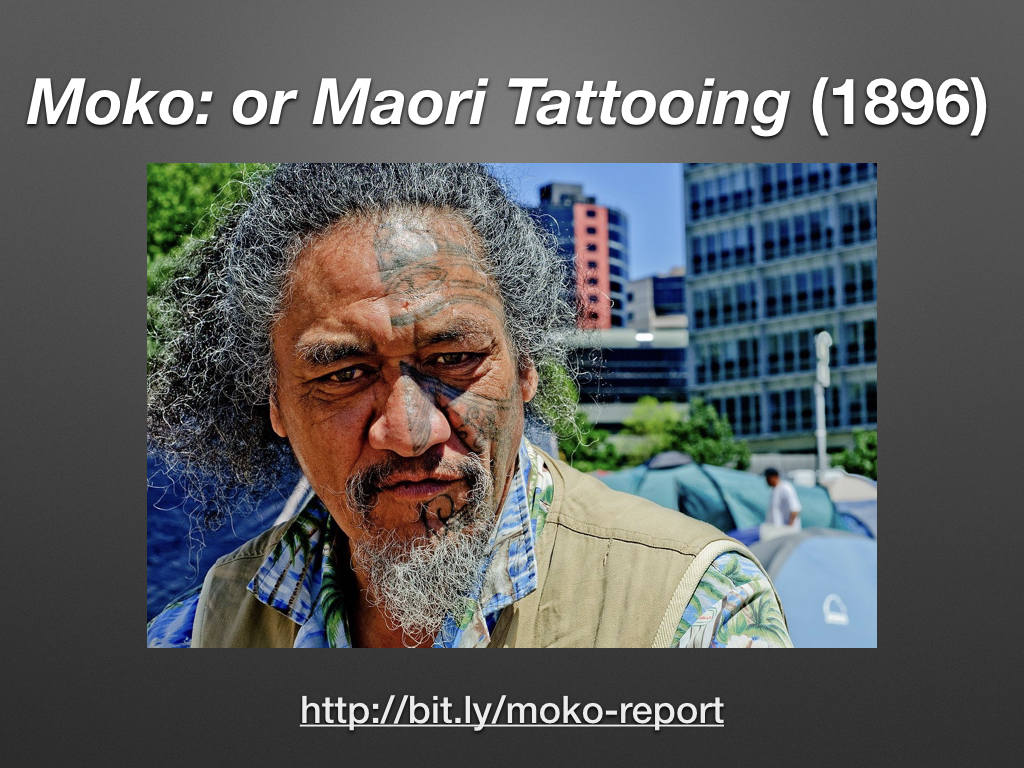

Moko: or Maori Tattooing (1896)

Moko; or Maori Tattooing was published in 1896 by Chapman & Hall in London. Horatio Gordon Robley wrote this book, and it contained many illustrations that he did of mokomakai. According to Wikipedia: “Mokomokai are the preserved heads of Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, where the faces have been decorated by tā moko tattooing. They became valuable trade items during the Musket Wars of the early 19th century.”

This is an important historical book for New Zealand so the New Zealand Electronic Text Collection wanted to digitize it. They wrote a thoughtful report that includes background information, outlines a range of digitization options, describes the community consultation process and concludes with the digitization path that they chose. I love that they’ve put their report online, which raises awareness of the issues that surround digitization of textual taonga, or cultural treasures.

The six perceived options for digitization ranged from:

- Present everything online.

- Provide access to all content except photographs of mokamokai.

- Provide access to all content except photos and line drawings of mokamokai.

- Provide access to all content except all photos of people and line drawings of mokamokai.

- Provide access to text only.

- Suppress everything.

They consulted with academics, librarians and curators, and with communities.

Academics were generally in favour of retaining the integrity of the book in the interests of scholarship by presenting all the content online.

Librarians and curators had a wide variety of opinions. Some concerns were “expressed about both the public display of images of ancestral remains and the potential for the moko themselves to be copied and used in inappropriate ways when made globally accessible online”. As parts of the book had been digitized by Google Books some felt that it was better that a New Zealand organization was digitizing New Zealand historical materials.

People from user and source communities also had a wide variety of opinions. One artist was against, it as he felt that wide dissemination of moko designs might result in others profiting from them. Suggestions were made that they should contact the family of those in the images to ask for permission to display them or to have a way of dealing with grievances and requests from family asking them to remove the images.

In the end they decided to present the text with all associated images except those depicting mokamokai or human remains. They also stated that they were open to altering their decision. They were willing to remove images of people’s ancestors as well as willing to add information about people’s ancestors.

Spare Rib

Michelle Morovec, a historian of women’s culture and digital history at Rosemont College in Philadelphia introduced me to this case study. Spare Rib was a UK feminist magazine that was published from 1972-1993. In 2013 the British Library wanted to digitize and put the entire magazine run online. Unlike a mainstream magazine, Spare Rib was edited by a feminist collective who didn’t necessarily get copyright clearances for things they published. The British Library hired a copyright clearance officer who worked with some members of the collective to track down over 4,000 authors and artists who had contributed to Spare Rib.

A contributor named Gillian Spragg wasn’t opposed to the content being digitized and put online, but she found the request that contributors agree to have their content licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial license to be problematic. She was worried that her feminist content could be remixed for anti-feminist purposes. In 2014 a law was passed that allowed “orphan works”, or work where the copyright holder can’t be found, to be digitized and the project went ahead. For each digital object there are clear rights statements. It’s also easy to find who to contact if you have more information about an object which I assume also includes if you know whose work it is, or if it’s yours and you want to have the licensed changed or have it removed from the website.

According to the British Library approximately 20% of the Spare Rib content has been removed from the website.

I love that they also have a page on Ethical Use acknowledge that the “usage guide is based on goodwill. It is not a legal contract. We ask that you respect it.”

Generate examples

What are some other examples of culturally sensitive materials in libraries, archives and museums?

You’ll have 4 minutes, 2 minutes each to talk. I’ll give you a time check halfway through.

Community led digital projects

Academic libraries can learn a lot from public libraries about how to work in community and with community.

In a toolkit on community-led libraries Annette DeFaveri talks about a time when she worked to build relationships with people in a homeless shelter and how it revealed some of her assumptions and biases. When she asked them what they might like from the library

One man said that he thought the library should give free courses in astronomy. Another person suggested that the library do astrology courses as well. Finally, someone else suggested that the library buy a telescope. This was a significant discussion for me and revealed many of the biases and prejudices I had brought to the work. I had expected people to talk about the importance of offering free coffee at the library or to discuss the dismal lack of wet weather beds in the community and ask what the library could do about that. I thought I would hear about all the issues that concerned me about homeless people in the community. After I left the shelter, I realized that the people I talked with had asked for things from the library that were relevant to their lives. They were interested in the night sky, astronomy, astrology and telescopes because they often slept outside and so spent significant amounts of time looking at the stars.

If the library worked with the community to co-create a digitization project from the start I think the process and the outcome could be awesome. Co-creation is much more than just consulting with the community on metadata, or tweaking a project that’s already done. It’s working with communities to identify the scope of the project, the process and what the final project will look like. We bring some knowledge of digitization, workflows and metadata, but I think we could let go of control a lot more and truly co-create with our communities. This could be transformative. Not just for the digital collections that we create, but for the relationships we have, and for libraries as a whole.

Problem solve

How can we do a better job of digitizing culturally sensitive materials?

Break into groups of 4 and discuss. Add your ideas to this Google Doc:

Conclusion

I work at a really wonderful community college. In preparation for this talk, I had a few meetings to make sure that speaking about being a former sex worker wouldn’t compromise or cost me my job. Both my director and faculty association president had awesome, supportive responses. I used to describe myself as lucky, but more and more I’m realizing that it’s not luck—it’s privilege. Because I have this privilege I have a responsibility to speak up about these things.

I’d like to end with another quote from Amber Dawn. She writes about a social experiment she ran in the 90s when she would answer the question “what kind of work do you do?” with “prostitution.” She observed that this made people uncomfortable and speechless. She writes:

While this little investigation was by no means sound research, it revealed a larger truth—that to listen to and include sex workers’ voices in dialogue is a skill that we have not yet developed, just as we have not learned how to include the voices of anyone who does not conform to accepted behaviours or ideas. What does it mean to be given the rare and privileged opportunity to have a voice? To me, it means possibility and responsibility. It means nurturing my creativity and playing with personal storytelling, while honouring the profound strength and dignity of a largely invisible population of workers and survivors. It means revelling in the groundbreaking work of voices that have come before me.

I’d like to ask you to listen to the voices of the people in communities whose materials are in the collections that we care for. I’d also like to invite you to speak up where and when you can. As a profession we need to travel the last mile to build relationships with communities and listen to what they think is appropriate access, and then build systems that respect that.

Thank you.

Image credits

All images are CC-BY except for The Land of Giants, fingerlove, and the Spare Rib covers.

- Choi+Shine Architects. The Land of Giants. http://www.choishine.com/Projects/giants.html (used with permission)

- Umbrella Trees: https://flic.kr/p/kAT3Ws

- Occupied http://imagicity.com/2011/10/27/occupied/

- fingerlove: https://www.photocase.com/photos/236919-hand-love-emotions-happy-funny-couple-photocase-stock-photo

- Spare Rib cover image March 1973 ©Estate of Roger Perry CC-NC (https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/spare-rib-magazine-issue-009)

- Spare Rib cover image October 1978 by Lynn Duncombe https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/spare-rib-magazine-issue-075

- M42 Orion Nebula: https://flic.kr/p/dSHFUN

- Microphone: https://flic.kr/p/axnVcw

![screenshot of ProQuests' Canadian Major Dailies datatbase with "Action plan on rights set up [Final Edition]" article](https://tararobertson.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/LITAforum.007.jpeg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.